Creative Systems Theory presents a comprehensive framework for understanding purpose, change, and interrelationship in human systems. It is radically significant both for the practical usefulness of its ideas and for the fact that it represents the kind of conceptual perspective that will be increasingly essential in times ahead. (See www.CSTHome.org.)

Many of the questions where CST offers greatest insight in some ways have to do with how human systems change and evolve. (See Patterning in Time.) For example, we can use the theory to help us understand why at different times in history we have seem our worlds in the ways we have—a topic with increasingly critical application as globalization brings cultures at different points in cultural development into dangerously explosive proximity. (In my book Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future, I argue that terrorism is impossible to effectively understand and address without an appreciation for cultural stage differences.) In a similar way CST helps us appreciate the unique worlds we inhabit at different stages in our personal development. For example, we can use it to understand why children believe in Santa Claus while adults don’t, and why adolescents behave in some of the apparently non-sensical and dangerous ways that they often do.

Other questions where CST provides important perspective have to do with here-and-now differences and interrelationships. (See Patterning in Space.) For example, it provides a unique depth of understanding of personality diversity. CST’s personality framework brings a valuable richness to self-understanding, offers important tools for effective communication and collaboration, and helps makes sense of an endless array of otherwise baffling observations. (See The Creative Systems Personality Typology.) One of the major limitations of contemporary education is that it fails to recognize this depth of human difference. Learning that effectively prepares students for the future will increasingly require it.

Many people find particularly intriguing how CST brings fresh perspective to eternally perplexing questions—for example, how is it that determinism and free will can be compatible, how scientific and spiritual truth ultimately relate, and how best to think about our place in the larger scheme of things (who we are in relationship to the purely physical and the biological). (My recent book Quick and Dirty Answers to the Biggest of Questions specifically addresses this aspect of CST’s contribution.) CST also helps make understandable why at different times and places in the human story we have answered such questions in the often remarkably different ways that we have.

Of most immediate and practical importance, CST helps us make sense of the times in which we live. The concept of Cultural Maturity, a key notions within Creative Systems Theory, argues that Modern Age institutions and ways of thinking are not the end points and ideals that we tend to assume them to be. It describes how the future is challenging us to engage a next, more fully “grown up” chapter in our human narrative. CST delineates why we should be seeing this further cultural chapter and helps us understand the new human capacities that Cultural Maturity’s changes make possible.

Rethinking Systems

The concept of Cultural Maturity in turn helps us appreciate the significance of ideas like those we find with CST. It is important to recognize that CST’s thinking is not just new, it reflects a critical leap in how we understand. Cultural Maturity’s changes alter not just what we think, but also how we think. They are products of a specific kind of cognition reordering (see next section). The fact that CST is able to address the kinds of questions just noted is a product of the conceptual leap that comes with Cultural Maturity’s cognitive changes.

How do we best understand that leap? Making sense of it starts with the recognition that culturally mature perspective helps us think in ways that are more encompassing—more systemic. We become able to understand in ways that better take everything involved into account. But there is more than just this, and the additional piece is critical. Cultural Maturity’s cognitive reordering makes possible a more dynamic kind of systemic understanding than we have been capable of grasping in times past.

Historical perspective helps clarify what more is involved. The kind of systems thinking we are used to is the gears-and pulleys sort used by good engineers to build bridges and computers. Learning to think in the language of machines—a contribution we most associate with the ideas of Newton and Descartes—was key to modern age advances. It was radical in the sense that it liberated us from much of the superstition and dogmatism of medieval belief.

But machine-language thinking, even if it attempts to be encompassing, will not be sufficient going forward. Certainly we need more than just engineering models if we are to deeply understand ourselves. We are not machines, we are living beings. And there is a further essential fact. Few of the critical challenges ahead of us species are amenable to purely technical solutions. They require us to rethink values and relate in ways that we are only beginning to understand. (See The Seven Questions On Which Our Future Most Depends.) For example, while new invention will obviously be critical in going forward, as or more important, ultimately, will be learning to ask more deeply what it means to use invention wisely. The most important question before us, in the end, are are questions of life—and more than this, questions that concern the very particular kind of life we are by virtue of being human.

Creative Systems Theory’s conceptual approach takes us beyond the mechanical systems thinking of a good engineer. It also takes us beyond an almost opposite kind of thinking that people can confuse with mature systemic thought—the naïve holism of more spiritual interpretations. In just how it does these things, it provides a way to address essential questions and have the concepts we use highlight the fact that we are living beings—and specifically human beings. Creative Systems Theory not only succeeds at making this essential leap in understanding, it offers a detailed set of “pattern language” tools for thinking with the needed new systemic sophistication.

The Power of a Creative Frame

The theory takes as its starting point the most basic question we could ask about ourselves: What is it that most makes us human? Is it that we use language? Is it that we have complex social structures? Creative Systems Theory proposes that what most defines us is the richness and audacity of our creative capacities. We are tool-makers. And we are not just makers of things, but also of ideas and social structures. And of particular importance, we are makers of meaning.

CST applies the word “creative” in a way that stretches beyond our usual use of the term. Here the word concerns art no more than science, nor the language of imagination any more than hard logic. (The more formal term in CST is formative process). But once the meaning of the word “creative” is expanded sufficiently, the term captures quite well what most fundamentally makes us who we are.

Alfred North Whitehead spoke of creativity as the “universal of universals.” CST observes something similar, then goes on use this observation to develop a general framework for making sense of human understanding—both understanding’s mechanisms and why we understand in the diverse and often contradictory was that we do. From CST’s vantage, not only are we tool-making creatures infinitely creative, how we think, act, and relate reflects underlying creative organization. CST describes how we also see creative organization in the structures we give our worlds—governmental forms, architecture, and the particular inventions that at any time we are capable of and willing to embrace. It applies the recognition that creative organization underlies that workings of human systems to help us better understand why we see our personal and collective worlds in the ways that we do, how such perception evolves over time, and the particular changes that are reshaping experience in our time.

CST proposes that human understanding has always been creative and delineates how this is the case. It also emphasizes that the ability to think more explicitly in creative terms is something wholly new—a product of Cultural Maturity’s cognitive changes. With these changes we becomes newly able both more fully step back from, and more deeply engage, the whole of how we understand. (See Cultural Maturity’s Cognitive Reordering.) The more encompassing vantage that results—what CST calls Integrative Meta-perspective—replaces the from-the-balcony perspective of objective knowing that has defined Modern Age understanding with a more dynamic and complete picture of who we are and how things work. A creative frame adds to this basic picture the recognition that human cognition is specifically structured to support our audaciously creative capacities. The result is an ability to not just to think more dynamically, but to do so in a way that is highly nuanced and detailed.

CST describes how the truth’s of each stage in culture’s evolution have drawn on specific aspects of our creative natures. It also delineates how different kinds of understanding—for example, that of science or art or business or religion—similarly draw on different aspect of our creative make-up. Integrative Meta-perspective makes it newly possible to appreciate these multiple aspects of our complex creative natures and to apply them in conscious and integrated ways.

A couple of conceptual “windows” in different ways provide deeper glimpses into this result. One is the increasingly recognized observation that intelligence is multiple. Integrative Meta-perspective helps us more deeply appreciate how intelligence has aspects and how these different aspects work together. CST goes further to describe how the various parts of human intelligence are structured specifically to support and drive our striking creative capabilities.

The other is the role polarity has traditional played in how we think. Integrative Meta-perspective allows us to step back and better appreciate that role. Again, CST lets us be more specific. It describe how the fact that we think in the language of polarity is a product of cognition’s creative workings. And it delineates how a predictable sequence polar relationships underlies the workings of formative processes of all sorts—from a simple act of invention to the evolution of culture.

Taking these complementary ways of thinking about creative organization one at a time helps begin to fill out CST’s contribution.

Integrative Meta-perspective, Creativity, and Intelligence

First, Integrative Meta-perspective helps us appreciate that intelligence has multiple aspects. There is rationality—in which we take appropriate pride. But there are also other ways of knowing such as the intelligence of feelings and emotions, of imagination, and of bodily experience that are ultimately just as important. (CST uses more specific language and makes finer distinctions, but these familiar terms are sufficient as a start.)

The implications of this simple recognition are huge. The ability to draw consciously on more of intelligence’s complexity makes possible more complete ways of understanding. By using the word “complete” I don’t mean finished. Rather, we become able to think in ways that better reflect all of who we are.

The ability to do so is becoming increasingly critical. Earlier I observed that important questions are more and more often not just technical questions, but questions of value and questions that require wisdom to address effectively. The intellect alone is great for questions that only require knowledge. Question of value, and, in particular, questions that challenge us to be wise, require Integrative Meta-perspective’s more complex kind of engagement.

The recognition that intelligence had multiple aspects was key to CST’s origins. Given all that Creative Systems Theory accomplishes, a person might assume that its development was motivated by some overarching desire on my part to influence social/political events, to address grand philosophical quandaries, or, at the least, to make original contributions. In fact, the roots of these notions are much more humble and the process that eventually brought them into being much less one of design.

In my teen years, I found special fulfillment in the creative arts—in particular sculpture and music. A bit later, I became increasingly fascinated with creative process itself—with how it is that things that matter come into being. Wanting to understand all I could about how creative process worked, I also began to research what had been written about it. I assumed that academic psychology had extensively studied the topic. To my great surprise, very little had been written, and almost all that had been written was superficial at best. I now better understand why I found this absence and recognize its important implications. But at that time all I knew was that I was going to be more on my own in this inquiry than I had expected.

A first recognition in this inquiry, while not original, was certainly important: Creative processes progress through a generally consistent sequence of stages. In my earliest writings, I documented these stages and some of the unique demands that come with each of them.

A further observation was more fully original and would prove of particular significance: I saw how each stage in formative process predictably involves a different kind of cognitive process. A simple way to think about it is that each stage draws preferentially on different aspects of intelligence and different relationships between intelligences.

Besides being key to making sense of creative process, this second observation also helped me understand why academic psychology had provided so little help. Academia is only beginning to question its Age of Reason assumption that truth—certainly truth of a theoretical sort—can always ultimately be described rationally. Restricted to rational analysis, what we can say about creative process is limited at best.

Over the next ten years, I found myself confronted by a series of further recognitions. I saw how we can observe a related progression of intelligence-specific creative stages with human formative processes of all sorts—not just invention, but also individual human development, how relationships evolve, and of particular significance, the chapters in culture’s larger story. This series of recognitions not only served as the foundation for CST, it would determine the course of my life’s work. Gradually my attention shifted from more personal and psychological concerns to issues of a more social and conceptual sort.

Creative Systems Theory describes how our various intelligences—or we might better say sensibilities to reflect all they involve—relate in specifically creative ways. And it goes on to delineate how different ways of knowing, and different relationships between ways of knowing, predominate at specific times in any human change processes. Our various modes of intelligence, juxtaposed like colors on a color wheel, function together as creativity’s mechanism. That wheel, like the wheel of a car or a Ferris wheel, is continually turning, continually in motion. The way the faces of intelligence juxtapose makes change, and specifically purposeful change, inherent to our natures.

A brief look at a single creative process—let’s take as example my writing of a book—provides clarification. In subtly overlapping and multi-layered ways, the process by which a book comes to be moves through a progression of creative stages and associated sensibilities. Creative processes unfold in varied ways, but the following outline is generally representative:

—Before beginning to write, my sense of a book is murky at best. Creative processes begin in darkness. I am aware that I have ideas I want to communicate. But I have only the most beginning sense of just what ideas I want to include or how I want to address them. This is creativity’s “incubation” stage. The dominant intelligence here is the kinesthetic, body intelligence, if you will. It is like I am pregnant, but don’t yet know with quite what. What I do know takes the form of “inklings” and faint “glimmerings,” inner sensings. If I want to feed this part of the creative process, I do things that help me to be reflective and to connect in my body. I take a long walk in the woods, draw a warm bath, build a fire in the fireplace.

—Generativity’s second stage propels the new thing created out of darkness into first light. I begin to have “ah-has”—my mind floods with notions about what I might express in the book and possible approaches for expression. Some of these first insights take the form of thoughts. Others manifest more as images or metaphors. In this “inspiration” stage, the dominant intelligence is the imaginal—that which most defines art, myth, and the let’s-pretend world of young children. The products of this period in the creative process may appear suddenly—Archimedes’s “eureka”—or they may come more subtly and gradually. It is this stage, and this part of our larger sensibility, that we tend to most traditionally associate with things creative.

—The next stage leaves behind the realm of first possibilities and takes us into the world of manifest form. With the book, I try out specific structural approaches. And I get down to the hard work of writing, and revising—and writing and revising some more. This is creation’s “perspiration” stage. The dominant intelligence is different still, more emotional and visceral—the intelligence of heart and guts. It is here that we confront the hard work of finding the right approach and the most satisfying means of expression. We also confront limits to our skills and are challenged to push beyond them. The perspiration stage tends to bring a new moral commitment and emotional edginess. We must compassionately but unswervingly confront what we have created if it is to stand the test of time.

—Generativity’s fourth stage is more concerned with detail and refinement. While the book’s basic form is established, much yet remains to do. Both the book’s ideas and how they are expressed need a more fine-toothed examination. Rational intelligence orders this “finishing and polishing” stage. This period is more conscious and more concerned with aesthetic precision than the periods previous. It is also more concerned with audience and outcome. It brings final focus to the creative work, offers the clarity of thought and nuances of style needed for effective communication.

—Creative expression is often placed in the world at this point. But a further stage—or more accurately, an additional series of stages—remains. It is as important as any of the others—and of particular significance with mature creative process. It varies greatly in length and intensity. Creative Systems Theory calls this further generative sequence Creative Integration. With the process of refinement complete, we can now step back from the work and appreciate it with new perspective. We become better able to recognize the relationship of one part to another. And we become more able to appreciate the relationship of the work to its creative contexts, to ourselves and to the time and place in which it was created. We might call creativity’s integrative stages the seasoning or ripening stages.

Creative Integration forms a complement to the more differentiation-defined tasks of earlier stages—a second half to the creative process. Creative Integration is about learning to use our diverse ways of knowing more consciously together. It is about applying our intelligences in various combinations and balances as time and situation warrant, and about a growing ability not just to engage the work as a whole, but to draw on ourselves as a whole in relationship to it. As wholeness is where we started—before the disruptive birth of new creation—in a certain sense Creative Integration returns us to where we began. But because change that matters changes everything, this is a point of beginning that is new—it has not existed before.

Creative Systems Theory applies this relationship between intelligence and formative process to human understanding as a whole. It proposes that the same general progression of sensibilities we see with a creative project orders the creative growth of all human systems. It argues that we see similar patterns at all levels—from the growth of an individual, to the development of an organization, to culture and its evolution. A few snapshots:

—The same bodily intelligence that orders creative “incubation” plays a particularly prominent role in the infant’s rhythmic world of movement, touch, and taste. The realities of early tribal cultures also draw deeply on body sensibilities. Truth in tribal societies is synonymous with the rhythms of nature and, through dance, song, story, and drumbeat, with the body of the tribe.

—The same imaginal intelligence that we saw ordering creative “inspiration” takes prominence in the play-centered world of the young child. We also hear its voice with particular strength in early civilizations—such as in ancient Greece or Egypt, with the Incas and Aztecs in the Americas, or in the classical East—with their mythic pantheons and great symbolic tales.

—The same emotional and moral intelligence that orders creative “perspiration” tends to occupy center stage in adolescence with its deepening passions and pivotal struggles for identity. It can be felt with particular strength also in the beliefs and values of the European Middle Ages, times marked by feudal struggle and ardent moral conviction (and, today, in places where struggle and conflict seem to beforever recurring).

—The same rational intelligence that comes forward for the “finishing and polishing” tasks of creativity takes new prominence in young adulthood, as we strive to create our unique place in the world of adult expectations. This more refined and refining aspect of intelligence stepped to the fore culturally with the Renaissance and the Age of Reason and, in the West, has held sway into modern times.

—Finally, and of particular pertinence to the concept of Cultural Maturity, the same more consciously integrative intelligence that we see in the “seasoning” stage of a creative act orders the unique developmental capacities—the wisdom—of a lifetime’s second half. We can also see this same more integrative relationship with intelligence just beneath the surface in our current cultural stage in the West in the advances that have transformed understanding through the last century.

We associate the Age of Reason with Descartes’s assertion that “I think, therefore I am.” We could make a parallel assertion for each of these other cultural stages: “I am embodied, therefore I am”; “I imagine, therefore I am”; “I am a moral being, therefore I am”; and, if the concept of Cultural Maturity is accurate, “I understand maturely and systemically—with the whole of myself—therefore I am.” Cultural Maturity proposes that the discussion you have just read about intelligence’s creative workings has been possible because such consciously integrative dynamics are reordering how we think and perceive.

Integrative Meta-perspective, Creativity, and Polarity

The second conceptual “window” for glimpsing how Creative Systems Theory accomplishes what it does turns to our tendency to think in polar terms. Prior to now, we humans have always thought in the language of polarity. We’ve spoken of allies and enemies, minds as apposed to bodies, and the spiritual set in juxtaposition to a separate material world. CST describes how we can think of the history of thought as an evolving sequence of time-specific polar juxtapositions.

Cultural Maturity’s cognitive changes fundamentally alter our relationship to polarity. They allow us to step back and be conscious of the fact that thinking in the language of polarity is what we have been doing. They also help us appreciate that while thinking in polar terms has worked—at the least it has served to simplify what would otherwise have been an overwhelmingly complex picture—doing so will not continue to benefit us. It is becoming possible—and essential—that we learn to think more systemically, in ways that view polarities as complementary aspects of larger systemic realities.

Culturally mature perspective invites us to think in ways that “bridge” what before have seemed obvious polar distinctions. Nothing more characterized the last century’s defining conceptual advances than how they have linked before unquestioned polar truths—such as matter and energy, masculine and feminine, and humankind and nature. “Bridging” is not an ideal term, though it helps keep things simple. What the term refers to is very different from adding or average, and certainly different from reducing complexity to spiritual oneness. Better we might refer to getting our arms around all that is involved. We are beginning to recognize how it is a bit strange that we would think of ourselves—or whatever we might reflect on—as anything but whole.

The application of a creative frame lets us take understanding a couple of steps further—each critically important. First it help us make sense of why we see polarity in the first place. CST proposes that that the fact that, through time, we have thought in the language of polarity is a product of our toolmaking natures and how creative processes inherently work. For anything new to come into being it must appear and distinguish itself from what has existed before—set this as opposed to that. (See Polarity and Creative Process.)

In addition, the theory describes how we can draw on polarity and its workings, like we can with the fact of multiple intelligences, to map how human systems creatively evolve and interrelate. At the heart of CST is a diagram it calls the Creative Function. The Creative Function describes formative process as an evolving interplay of polar relationships. The Creative Functions provides a generic representation of formative dynamic of all sorts. The whole of CST can be understood in relationship to it.

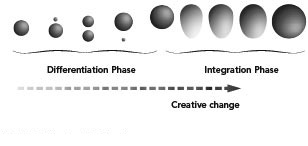

The Creative Function depicts formative process has having two halves—a differentiation phase and an integration phase. Formative processes start from nothing (or more accurately a context). With creative differentiation, new possibility buds off and takes increasingly manifest forms. With creative integration the newly created form reintegrates with its context, becoming part of an expanded picture of “how things are” (and as experience becoming increasingly “second nature”). CST proposes that Cultural Maturity’s changes reflect the beginning of this second, more integrative aspect of formative process as it manifests in culture as a creative process. One result is that we become newly able to appreciate the ultimately creative nature of human understanding.

CST uses this basic recognition of creatively-organized polar patterning to develop detailed systemic formulations. The picture that results helps us appreciate not just how understanding changes, but also how, in the way understanding changes, everything else about us changes as well—how we relate one to another, what we believe, and what ultimately creates the human experience of purpose.

Creative Systems Patterning Concepts

Whether our focus is intelligence’s multiplicity or polarity’s role in how we think, the result is the same. Step back, and we see how our remarkable creative capacities are what make us unique. We recognize that to be human is to be engaged in a constant process of shaping ourselves, our human connections, and the physical worlds around us. We also see how creation is about much more than some rabbit-out-of-hat process of innovation, or just about new insights. We recognize how it is highly and specifically patterned.

CST describes how a similar sequence of evolving creative relationships orders human developmental processes of all sorts. It goes on to describe how here-and-now relationships in human systems can similarly be thought of as creative. Human systems are creative not just in how they change, but in how their internal parts are structured, how those parts interrelate, and how various systems engage one with another. Whether the whole that concerns us is an individual, a relationship, an organization, or a society, in the end what we engage is a creative whole.

In application, CST employs three kinds of creatively-framed “patterning concepts,” what it calls Whole-Systems patterning concepts. Patterning in Time concepts, and Pattering in Space concepts. It also makes use of a handful of additional concepts that help in making sense of current cultural changes and with the critical task of separating the conceptual wheat from the chaff as we look to the future.

Whole-System Patterning Concepts address what truth at its most basic becomes when cultural guideposts no longer provide reliable direction. They make what CST calls culturally mature “crux” distinctions. In different ways, their interest lies with the degree an act or idea is “life-giving”—in the language of formative process, the degree it supports and enhances our creative growth and well-being. Whole-System Patterning Concepts address questions like purpose, morality, capacity, and violence. While less immediately provocative than creative truth’s two more differentiated sorts of concepts, many people find them in the end the most transforming in their implications. *Patterning in Time and Pattering in Space concepts address difference in dynamically systems terms. They make what CST calls culturally mature “multiplicity” distinctions. Patterning in Time and Patterning in Space concepts share that their concern is parts, distinctions not just between the “how much” of systems, but between the “whats, the whys, and the how manys.” To use a painting analogy, they address the colors available on the palette (or to be more precise, this plus when and where colors are most usefully applied).

Patterning in Time is just what it sounds like—though time in this sense refers not just to clock time, but to developmental time. Patterning in Time concepts help us make sense of underlying processes in human growth (including not just individual growth but also the growth of relationships), predict change dynamics in organizations, and better understand how various realms of human inquiry—science, government, education, religion—have evolved over time. Of particular significance for today, they provide perspective for making sense of the changes that define our time. Patterning in Time concepts describe how what makes a system creatively vital very much has its seasons. Whether our concern is the span of a creative project, the duration of a relationship, a personal lifetime, or the story of culture, different stages not only give voice to very different truths, they reflect very different notions about what makes something true. Patterning in Time concepts describe how various scales of formative process layer one atop the other and together define the context of any creative moment. (See Creative Scales.)

Patterning in Space concepts address here-and-now systemic interrelationships. We can use them to make sense of our own internal workings, to better understand relationships of every sort (from intimate bonds to the bonds of communities, institutions and nations), and of particular pertinence for today, to teasing apart the complexly interrelated implications of our present human condition. Patterning in Space discriminations address creative relativity in the here and now—one’s place in a system’s diversity. They describes how our inner and outer worlds are each profoundly plural. CST’s framework for understanding temperament diversity is its most well-known Patterning-in-Space contribution. (See the Creative System Personality Typology.)

Simplicity and Complexity

There are ways in which CST is decidedly more complex than usual conceptual approaches. Certainly it pushes into new territories of understanding. It also requires us to take much more into account than is generally our practice. And its concepts are more nuanced and detailed than more familiar notions.

But there are also ways in which it is simpler than approaches we commonly use. Albert Einstein once commented that all his ideas had their origins in a single question from his youth: What would the world look like if seen from atop a beam of light? In a similar sense, CST organizes around a single question: What does the human experience look like when viewed as a reflection of our creative natures? Every one of CST concepts can be seen to follow directly from this simple question. (Note how this fact, by creating separation between the theory’s ideas and the beliefs of its author, invites others to contribute to the theory’s evolution. Anyone can take that core question and argue for particular implications.)

The fact that all of CST’s distinctions follow from the recognition of formative patterning also results in an important practical kind of simplicity. Learning how to make one kind of discernment takes us a long way toward understanding how to make them all. And, if CST is right, that single fundamental patterning dynamic is not foreign to us, though we have not before been conscious of just how it works. At some level, we’ve been making these kinds of distinctions since our species’ beginnings.

CST goes on to argue that such patterning is not only familiar, in a sense it is inevitable. It follows directly from the fact of conscious awareness (and its purpose, that we might be tool-makers—“creative” at a new depth and constancy). It is not some invention of conscious awareness, a handy choreography designed for that task. Rather it is how creation necessarily works. Any formative process follows a predictable progression. The mechanism doesn’t need design. There really isn’t much other way to go about it. Be tool-makers, and this is pretty much how it has to work.

It is important to distinguish what CST concepts are good for and what they are not. Their contribution lies with questions of underlying pattern. Much in the particulars we observe may have different origins. For example, personality style differences explain only part of why a person may act the way he or she does. As important are personal idiosyncrasies and life events that may have nothing to do with temperament—or anything else a creative perspective has much to say about. And while aspects of what we see in a culture’s artistic forms, religious beliefs, and governmental structures reflect cultural stage, as much is a result of essentially arbitrary historical events and, again, numerous effects for which creative mechanisms at any level play little if any significant role.

But limitations acknowledged, CST presents a powerfully useful set of tools. The recognition of underlying patterns is often what is most missing in modern thought. When our concern is purpose—as it must more and more be today as traditional guideposts fail us—questions of how experience organizes necessarily move forefront. Recognition of pattern provides the big-picture perspective needed to make our choices about particulars in ultimately useful ways.

In George Orwell’s 1984, his character Winston Smith observed that too often he understood the “how,” but not the “why.” Today, we tend most often to not really even get to the “how.” Both the evening news and our familiar depictions of history commonly reduce to an accumulation of “whats.” CST is specifically about “how.” And even more specifically, in a sense that becomes possible only with culturally mature perspective, it is about “why.”

—-

[Numerous resources exist for learning about Creative Systems Theory. On-line, the Creative Systems Theory website (www.CSTHome.org) provides a detailed look at CST patterning concepts. The Cultural Maturity blog (www.culturalmaturityblog.net) provides ongoing application of Creative Systems Theory concepts to critical current issues. And the main Institute for Creative Development website (www.creativesystems.org) includes links to an array of Creative Systems Theory–related sites for those who wish more in-depth understanding.Various of my books through the years have come at making sense of culturally mature perspective and the implications of creative frame from different angles. The Creative Imperative (1984) first introduced Creative Systems Theory and remains the most definitive resource for many of the theory’s concepts. Necessary Wisdom (1991) took the Creative Systems Theory observation that thought able to effectively address future questions “bridges” familiar polar juxtapositions (such as us versus them, mind versus body, or masculine versus feminine) and used it to address tasks ahead in various realms of understanding. My more recent books give particular attention to the concept of Cultural Maturity. Hope and the Future: An Introduction to the Concept of Cultural Maturity is a short work designed to provide an accessible starting point for people new to the concept. Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future (with an Introduction to the Ideas of Creative Systems Theory) is a lengthy effort written for change agents and leaders wanting to explore Cultural Maturity’s challenge in greater depth and detail. Quick and Dirty Answers to the Biggest of Questions: Creative Systems Theory Answers What It is All About (Really) examines the proposal that answers to many of humanity’s most elusive questions have eluded us not because the questions are inherently difficult, but because we need culturally mature perspective to effectively make sense of them. It goes on to use a creative frame to address many of the most important such “ultimate quandaries.”]