Cultural Maturity is much more than a metaphor for what the future asks of us. It reflects critical changes not just in what we think, but how we think, a necessary—and developmentally predicted—cognitive reordering. Creative Systems Theory calls the new vantage for understanding that this reordering produces Integrative Meta-perspective.

Integrative Meta-perspective makes it possible to think in ways that are more encompassing—more systemic. It involve both more fully stepping back from our diverse cognitive aspects and more deeply engaging them (see Cultural Maturity’s Cognitive Reordering). Because the understanding that results is more complete, it has the potential also to be more wise.

We can approach making sense of Integrative Meta-perspective in different ways. We can think of it in terms of the new capacities it makes possible (see Cultural Maturity’s Defining Themes). We can also examine how the ideas that result differ from those we find with other ways of thinking (for example, see Scenarios for the Future). But we can also address the cognitive changes themselves. We can examine how Integrative Meta-perspective helps us engage and draw on the whole of our cognitive complexity.

This last way has particular importance if we wish to understand Integrative Meta-perspective deeply. It is not as simple as we might wish. We face the inescapable “Catch 22” reality that we need Integrative Meta-perspective to fully grasp what our “cognitive complexity” involves, much less hold it in a culturally mature way. But this approach lets us be very specific about what produces Cultural Maturity’ changes and why those changes take us where they do.

Here I will describe three different ways to think about cognition’s aspects and what it means to hold them more systemically: understanding intelligence’s multiplicity, “bridging” polarities, and the more hands-on approach I call simply “parts work.” Each of these approaches has particular strengths. With each, I will first introduce the notion and some of the particular ways it helps us. I will then include a lengthier description adapted from my book Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future that fills out its implications.

Intelligence’s Multiplicity

The first way to think about cognition’s complexity—and how it relates to Integrative Meta-perspective—turns to the fact that human intelligence has multiple aspects. Integrative Meta-perspective makes it newly possible to draw on all of our multiple ways of knowing and appreciate how they work together to make us who we are. *Creative Systems Theory puts these changes in historical context. It describes how different kinds of intelligence have been most defining at different times in culture’s story (see Intelligence and Creative Change). With Modern Age thought, we came to think of rationality as intelligence’s last word. Creative Systems Theory makes clear that further, more specifically integrative ways of thinking are critical if we are to continue to progress.

One of the key strengths of thinking about Integrative Meta-perspective in terms of intelligences is how clearly doing so distinguishes culturally mature thought from what we have known (see Rethinking How We Think: The Critical Role of Multiple Intelligences). In contrast to more familiar ways of thinking, culturally mature concepts necessarily draw on multiple intelligences. Certainly this is the case with the ideas of Creative Systems Theory. For example, Creative Systems Theory emphasizes that it is really not possible to understand either how culture has changed over time or differences in personality style without an appreciation for intelligence’s multiplicity. No concept within Creatives Systems Theory is fully understandable without the engagement of intelligence as a whole.

In Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future, I use this ways of framing cognition’s complexity to introduce the idea of Integrative Meta-perspective: “Integrative Meta-perspective involves two, almost opposite processes. We see both of them, simply at difference scales of significance, with personal maturity and Cultural Maturity. The first produces greater awareness, a more complete kind of stepping back. The second produces the new depth of engagement needed if the result is to be not just further abstraction, but the deeply embodied kind of understanding that is needed for mature—wise—decision-making. Each kind of process is new, the first certainly in its implications, the second more fundamentally.

The first process, that more complete stepping back, at least differs from what we have seen in times past in all it involves. With Cultural Maturity we become newly able to step back from ourselves as cultural beings. We also step back from dimensions of ourselves that in times past did not allow such perspective.

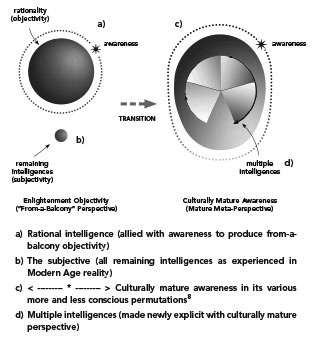

How we come to relate to intelligence’s various aspects provides good illustration of this first way of thinking about Integrative Meta-perspective. Enlightenment thought similarly had its origins in a new kind of cognitive orientation. Stepping back from previous ways of knowing was a big part of it. We came better able to step back from the more mystical sensibilities that had given us the beliefs of the Middle Ages.

Along with this more general stepping back, rationality came to assume a newly central significance. The rational now stood clearly separate from the subjective aspects of experience and became specifically allied with conscious awareness. The resulting, as-if-from-a-balcony sense of clarity and objectivity, along with the new belief in the individual as logical choice-maker that came as a consequence, produced all the great advances of the Modern Age.

But while Enlightenment perspective was a grand achievement, Integrative Meta-perspective’s stepping back represents a different sort of accomplishment. With Cultural Maturity, awareness comes to stand more fully separate from the whole of our intelligence’s systemic complexity—including the rational.

Integrative Meta-perspe ctive offers that we might step back equally from aspects of ourselves that before we might have treated as objective and those that we before thought of as subjective. In the process it offers that we might better step back from the whole systemic ball of wax whatever our concern. *The second kind of process is not just different from what we have known, it finds no parallel at all in earlier developmental changes. Along with stepping back, Integrative Meta-perspective engages who we are with a new depth and completeness. It involves a newly possible connectedness with the full complexity of human experience. The result is Cultural Maturity’s more complete, more embodied engagement with experience.

ctive offers that we might step back equally from aspects of ourselves that before we might have treated as objective and those that we before thought of as subjective. In the process it offers that we might better step back from the whole systemic ball of wax whatever our concern. *The second kind of process is not just different from what we have known, it finds no parallel at all in earlier developmental changes. Along with stepping back, Integrative Meta-perspective engages who we are with a new depth and completeness. It involves a newly possible connectedness with the full complexity of human experience. The result is Cultural Maturity’s more complete, more embodied engagement with experience.

We appropriately ask just what we newly engage with. Ultimately what we newly engage is the whole of ourselves as systems. Again, this has multiple aspects, but for our purposes it works to keep things simple and continue to focus on intelligence’s multiplicity. What we more deeply draw on is the whole of intelligence—all the diverse aspects of how we make sense of things.

Culturally mature understanding requires the conscious involvement of more aspects of intelligence—more of our diverse ways of knowing—than before we’ve applied in one place. This necessitates not just that we be aware that intelligence has multiple aspects, but that in a new sense we engage, indeed embody each of these aspects. Put in the language of systems, systemic perspective of a culturally mature sort requires that we consciously draw on the whole of ourselves as cognitive systems. Culturally mature understanding requires thinking in a rational sense—indeed, it expands rationality’s role. But just as much it requires that we more directly plumb the more feeling, imagining, and sensing aspects of who we are. And this is so just as much for the most rigorous of hard theory as when our concerns are more personal.

In a more limited sense we have always drawn on all aspects of intelligence. In doing a math problem, talking with a friend, or painting a picture, we tap very different parts of our neurology. But culturally mature understanding requires both a more aware relationship to our multiple ways of knowing and the ability to apply them in more sophisticated and integrated ways.

Note one important consequence of this new picture: Culturally mature perspective, while it produces less once-and-for-all kinds of truth than we have been accustomed to, is ultimately more objective than what it replaces. Enlightenment thought might have claimed ultimate objectivity, but this was in fact objectivity of most limited sort. Besides leaving culture’s parental status untouched, it left experience as a whole divided—objective (in the old sense) set apposed to subjective, mind set apposed to body, thoughts set apposed to feelings (and anything else that does not conform to modernity’s rationalist/materialist worldview). We cannot ultimately claim to be objective if we have left out half of the evidence.

Culturally mature “objectivity” is of a more specifically whole-ball-of-wax sort. Making sense of most anything about us—the values we hold, the nature of identity, what it means to have human relationship—today increasingly requires systemic understanding. Integrative Meta-perspective helps us appreciate just why this might be so. It also helps us recognize how such more mature and complete understanding might be an option.

“Bridging” Polarities

Another way to think about cognition’s complexity proves particularly helpful when it comes to making sense of how Integrative Meta-perspective alters where thought takes us. Always before in culture’s story, we’ve understood truth in terms of qualities set in polar juxtaposition—us versus them, mind versus body, science versus religion. Integrative Meta-perspective helps us at once step back from and more deeply engage these juxtaposed elements. We become able to appreciate them as aspects of larger system realities.

Creative Systems Theory helps make sense of how this is so. It proposes that the fact that we think in polar terms in the first place is a product of how formative processes inherently work. It also maps how polar aspects have juxtaposed in different, creatively predictable ways with each stage in culture (see Patterning in Time). Specifically with regard to Cultural Maturity, it delineates how the ability to hold these dialectical relationships more systemically is a predicted attribute of Integrative Meta-perspective.

I used this new ability to “bridge” conceptual polarities as the organizing concept for my 1991 book Necessary Wisdom. Each chapter in the book applies “bridging” to a different kind of concern—from global conflict, to intimacy, to morality. The recognition that Integrative Meta-perspective leaves behind the polarized assumptions of times past provides one of the simplest ways to grasp how understanding becomes different with Cultural Maturity’s changes. It also provides a compact way to distinguish culturally mature thought from ways of thinking we might confuse it with.

The following brief summary is adapted from Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future: “One of the most useful ways to think about how culturally mature perspective changes how we understand draws on a basic observation: Needed new understandings of every sort require that our thinking create links, “bridges”—and not just between phenomena we’ve regarded as different, but often between things that before now we’ve treated as complete opposites—as polarities.

F. Scott Fitzgerald proposed that the sign of a first-rate intelligence (we might say a mature intelligence) is the ability to hold two contradictory truths simultaneously in mind without going mad. His reference was to personal maturity. But this capacity is such an inescapable part of culturally mature perspective that we could almost say it defines it.

Effective global policy requires “bridging” ally and enemy. It also bridges political ideologies and, in the end, even usual ideas about war and peace. Mature gender identity and love link masculine with feminine, and individuality with connectedness. New approaches to leadership create bridges between leaders and followers, and as needed greater transparency occurs, bridges also appear between the internal worlds of organizations and between organizations and the larger world. The needed new kinds of relating, values, and understanding don’t require that we consciously recognize that bridging is taking place, or even that polarities are involved. But they do require that we somehow get our minds around a larger picture and act from it.

We can think of Cultural Maturity’s point of departure as itself a bridging dynamic: We step back and see the relationship of culture and the individual in more encompassing terms. Cultural Maturity bridges ourselves and our societal contexts (or put another way, ourselves and final truth). It is through this most fundamental bridging that we leave behind society’s past parental function.

It is important that we not misinterpret this. Cultural Maturity is not about culture’s role disappearing. Rather it is about a new and deeper recognition of how individual and culture relate—about how, through our thoughts and actions, we create culture, and how personal and cultural realities each inform the other. It is also about making our understanding of both being an individual, and being an individual who lives in an interpersonal context, more dynamic and complete (see Beyond Culture As Parent).

This most encompassing linkage holds within it a multitude of more local “bridgings.” Nothing more characterized the last century’s defining conceptual advances than how their thinking linked previously unquestioned polar truths. Physics’ new picture provocatively circumscribed the realities of matter and energy, space and time, and object with its observer. New understandings in biology linked humankind with the natural world, and by reopening timeless questions about life’s origins, joined the purely physical with the organic. And the ideas of modern psychology, neurology, and sociology have provided an increasingly integrated picture of the workings of conscious with unconscious, mind with body, self with society, and more.

Recognizing the fact of polarity by itself is not new. Our familiar Cartesian worldview is explicitly dualistic. Nor is the idea that polarity might be pertinent to wisdom new. That is, in fact, a quite ancient recognition. Epictetus observed that “Every matter has two handles, one of which will bear taking hold of, the other not.” But what I describe here is new, and fundamentally.

In modern times, even if we have acknowledged the basic fact of polarity, most often we’ve missed that the sides of polarity might relate. And certainly we’ve missed that they might relate in ways that produce today’s needed more mature and complex picture. We’ve assumed that it is right to think of minds and bodies as separate even though daily experience repeatedly proves otherwise. And we’ve accepted that a world of allies and “evil empires” is just how things are even as one generation’s most loathed of enemies becomes the next generation’s close collaborator.

The fact that we could miss polarity’s larger picture might seem odd. Why would we assume that reality is anything but whole? It turns out that there is a good reason. In fact, polar perception has an essential developmental function—in human change processes of all sorts. Indeed, it is critical to the mechanisms of development.

Implied in this is the essential recognition that the “problem” with polarity is not an intrinsic difficulty. Rather it is an expression of where we reside in the story of understanding. In times past, polarity worked. The polar tensions between church and crown in the Middle Ages, for example, were tied intimately to that time’s experience of meaning. With the Modern Age—and just as right and timely in their contributions—we saw Descartes’ cleaving of truth into separate objective and subjective realities, along with the competing arguments of positivist and romantic worldviews. And while I emphasize the outmodedness of petty ideological squabbles between political left and political right, I am comfortable proposing that such squabbles, in their time, were creative and essential. They drove the important conversations. The problem is not with polarity itself, but with its inability in our current time to effectively generate truth and meaning.

If the relationship between “bridging” and complexity is to make ultimately useful sense, we must take care to avoid confusing “bridging” in this sense with a couple more familiar outcomes. Bridging as I am speaking of it is wholly different from averaging or compromise, walking the middle of the road. And just as much it is different from simple oneness, the collapsing of one pole into the other as we commonly see with more spiritual interpretations. Bridging, as I use the word, is about consciously engaging the larger whole-ball-of-wax picture.

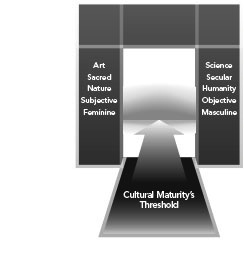

I often make use of a simple diagram to emphasize these differences. It depicts Cultural Maturity’s threshold as literally a doorway, with each side of the doorway’s frame representing one half of a polar relationship:

The term “bridging” might seem to suggest that our interest lies with joining the doorway’s two sides. But something quite different is necessarily involved. The doorway’s lintel could adequately represent either of our two misinterpretations. But joining the doorway’s two sides leads us nowhere—certainly nowhere pertinent to our desired destination. Cultural Maturity’s changes require that we make our way up to the doorway, step over the doorway’s threshold, and proceed into a reality that is not just more inclusive, but of an entirely different sort. Bridging in this sense we have interest in reflects this wholly different sort of action.

A good place to recognize such bridging’s fundamental newness is the way culturally mature conclusions can on first encounter seem paradoxical. Such apparent paradox is most obvious with ideas that are not so much about us—for example, how cutting-edge notions in physics are perfectly comfortable with something being at once a particle and a wave. But it is just as inescapably present with explicitly human concerns. Mature love makes us both more separate and more deeply connected; mature leadership is both more powerful and more humble than what it replaces.

Culturally mature perspective makes clear that this paradoxical appearance, again, is nothing mysterious. It simply reflects polarity’s necessary role in how we think. Blindness to polarity constrains us within a world of absolutes (and projections). Cultural Maturity’s threshold highlights the existence of polarity and alerts us to the fact that a polar picture is inadequate. Step over that threshold and into mature territory and things become more of a whole—a more dynamic and multifaceted kind of whole than we are used to, but also one in which the opposites of paradox are not ultimately at odds.

It is essential to recognize that bridging in this sense makes us more. And today it makes us more in exactly the “idea whose time has come” sense essential to a vital and healthy future. We can put the result specifically in terms of complexity. Bridgings of any sort take an either/or world and replace it with a picture that is more multi-hued and rich in its implications than we could have understood in times past.

We find the same result whether the defining polarity is conceptual or one that serves to order values and relationships. Bridge matter and energy and the result is a world of intricately interrelated particles and forces ever-surprising in what they have to reveal. Bridge ally and enemy and we find a world of people who share a common humanity, but who at the same time often remain profoundly foreign to our understanding—in wonderful and particular ways. In this new reality, complexity cannot be escaped, and past, more limited ways of understanding gradually lose their appeal. When bridging is something we are ready for, we experience what it reveals as a gift—and one of ultimately profound significance.

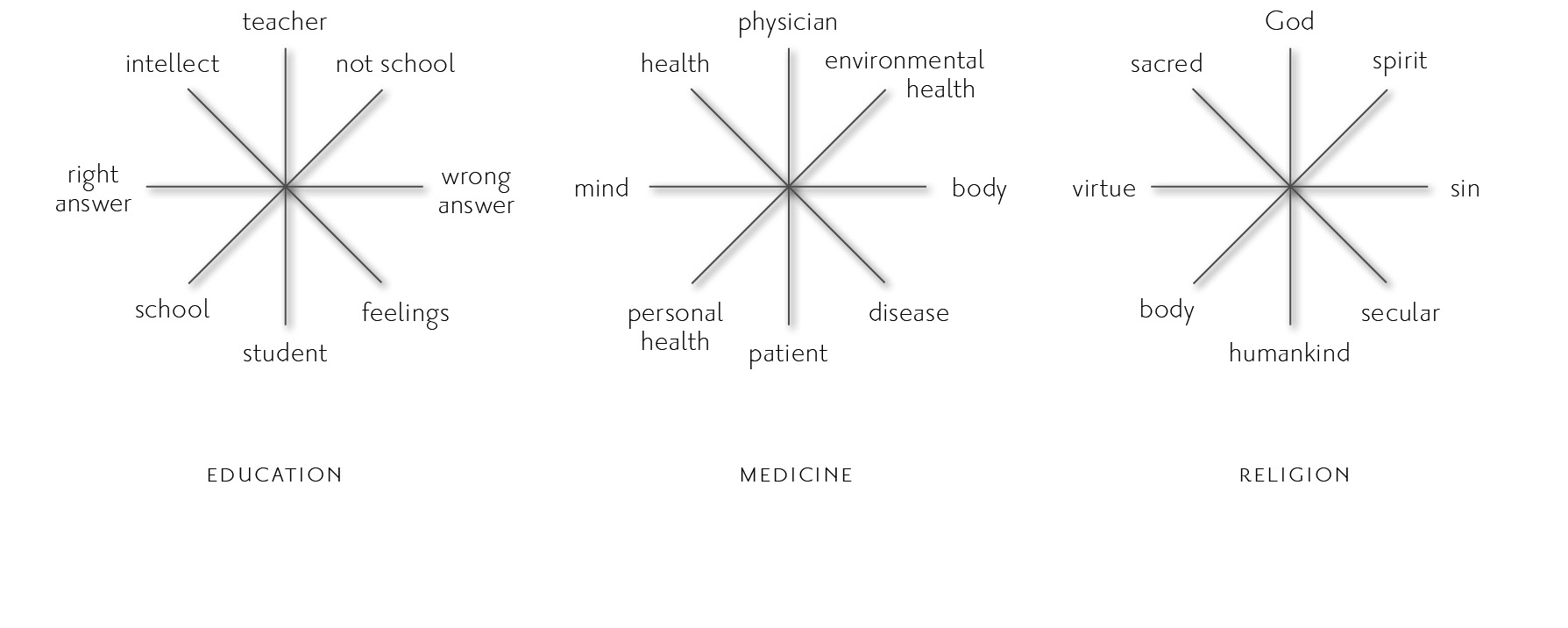

Besides helping us reframe questions in culturally mature terms, the notion of “bridging” provides one of the simplest ways to distinguish culturally mature thought from ways of thinking we might confuse it with (see Polar Fallacies). It also provides a way to map larger change process within whole domains of understanding. If we can identify the various polar juxtapositions that have ordered past ways of thinking in say education or medicine, we can then ask ourselves what it might look like if we engaged each of those either/ors in more encompassing and integrative ways.

“Parts Work” and Cultural Maturity’s “Cognitive Rewiring”

The third way to think about cognition’s complexity might at first seem more metaphorical and fanciful. But in fact it lets us be particularly precise. We can think of cognition’s various parts like characters in a play or crayons in a box. I draw on this way of thinking about cognitive aspects with approaches I use in trainings, and also as a therapist with individuals. I call these approaches simply “parts work.”

Parts work takes sophistication to execute well, but it is ultimately not complicated. It engages people in learning to hold and creatively apply the whole of themselves—to effectively draw on all the characters in the play/crayons in the box. Parts work has particular significance because it provides a methodology that directly supports Integrative Meta-perspective. It also in a further way fills out just where Integrative Meta-perspective takes us. We can think of parts work as providing a hands-on definition for Cultural Maturity’s changes.

Up until now in culture’s evolution, we’ve tended to view the world from the perspectives of particular characters/crayons. For example, with Modern Age romantic love, we relate from a “handsome prince” part of ourselves and engage a “fair maiden” part in another (or the reverse). With Modern Age leadership we act from a heroic part in ourselves and engage a dependent, follower part in another (or the reverse). With Integrative Meta-perspective, we become newly able to perceive and act from the whole of who we are. Two-haves-make-a-whole relationships give way to the possibility of more Whole-Person bonds. Identity becomes systemic—fully encompassing—in a way that has not before been an option (see A New Meaning For Love, Rethinking Leadership, and The Myth of Individuality). Parts work provides a way to directly promote these changes.

We can think of parts work taking each of the two previous ways of understanding cognitive complexity to a next level of sophistication. With regard to multiple intelligences, parts work let us get beyond just thinking about different ways of thinking and directly engage them. Various characters/crayons embody different aspects of intelligence. And the process itself, rather that just being analytic or just emotion-based as we commonly find with traditional psychotherapeutic approaches, draws simultaneously on all aspects of intelligence’s multiplicity.

The method also helps us get beyond traps commonly encountered when using polarity as a way to think about complexity’s aspects. Polar aspects take expression as parts. In doing parts work one establishes a new kind of relationship with parts. Parts don’t get to take over. But neither does one seek some middle ground between parts. One learns to lead from oneself as a whole person and draw on parts as creative aspects. When I wrote Necessary Wisdom I thought the idea of “bridging” polarities would provide an easy way for people to grasp culturally mature perspective. Sometimes it does, but even when I include diagrams and explanation like those in the previous section, very often people confuse “bridging” with oneness or compromise. These distinctions are built into parts work’s more hands-on approach.

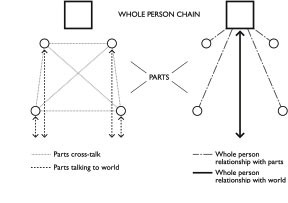

To appreciate these benefits, it helps to look briefly at some of the specifics of parts work. Imagine sitting in a chair (this is the Whole-Person identity chair) and placing your most important parts around you in other chairs (perhaps an intellectual part, an angry part, a scared part, a sensitive part, a sexual part). Parts work starts with learning to distinguish yourself from your parts. Prior to doing the work, it is common for parts to in various ways take over, engage the world as if they are us.

Parts work’s “rules” support this first step. The first cardinal rule in parts work is that parts don’t get to be in charge. The second cardinal rule is that parts don’t get to relate to the world, only with the Whole-person identity chair. These rules are modeled in the room in my relationship with the person I am working with. For example, I take care to relate only to you in the Whole-Person identity chair. They are also reinforced in the structure of the work.

A snapshot of how a session might proceed takes us a bit further: If you have a question you would like to explore, I might have you first articulate the question as best you can to your parts. I might also have you tell the parts where you have gotten to thus far in answering the question. Then I might invite you to get the input of each part, to, in turn, go to each chair and see what it has to say. Finally, after giving you some time to reflect, I might suggest that you to make a “leadership statement” to the parts summarizing how your thinking has involved through your engagement with them.

Notice that there are two kinds of processes implied in this simple description. Each is key to Integrative Meta-perspective’s changes. First is that which I have described— learning to know the difference between yourself when you are in the Whole-Person identity chair and when you are in a part. This first kind of process involves separation and distinction. The second kind of process is reflected in the ensuing conversations. It involves a new and deeper kind of engagement with parts. Using the box-of-crayons metaphor, the first is about not confusing yourself with particular crayons. The second is about learning to appreciate and draw on all the various colors.

This dual process helps bring more systemic perspective to the question you wished to explore. But with time, applied to many questions, and not just personal questions, but also questions of a more social/cultural sort, it brings about a more important result—Cultural Maturity’s needed cognitive reordering. We can think of the result as a kind of “rewiring.” Before doing the work, “wires” go from parts to the world. Afterward, “wires” go between parts and the Whole-Person identity chair only. Just the Whole-Person identity chair has a relationship with the world. And there is another rewiring piece. Before doing the work, “wires” also go back and forth between parts (this cross-talk is what creates chatter in our brain and is reflected in various forms of internal conflict). A third cardinal rule is that parts don’t talk to parts. “Wires” between parts, like those between parts and the world, are in a similar way cut.

The following excerpt adapted from Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future presents an example of parts work. The example comes from individual therapy done with a respected biologist and environmentalist. It starts with work at a personal level, but then transitions to address perspective needed more broadly for effective culturally mature leadership. The excerpt concludes by describing how the use of parts work can be expanded to different kinds of settings:

“Bill’s father had died. The immediate reason Bill had come to me was the depression that the loss had evoked. But with time, along with addressing grief, he recognized a further concern—what he described as a war within himself.

Bill’s father had left him a beautiful piece of land that had been in the family for generations. Bill loved the place and planned to construct a cabin and move there when he retired. But new zoning regulations had made the land unbuildable. Suddenly, his plans were on hold. He felt deeply sad—and angry. The particular situation disturbed him, but even more disturbing to him ultimately was the way his response to it had left him torn from the comfortable moorings of a once-unquestioned set of beliefs. He was known for banging heads with property rights proponents and more often than not emerging victorious. Now disparate internal voices were advocating not just different social policies, but two very different—and contradictory—views of the world. Bill found distress and confusion in this conflict and asked if we could somehow explore it.

I agreed. But I recognized that such work would present some difficulties. Bill was an exceptionally intelligent man with well-thought-out beliefs that were not easily questioned. We would have to do more than just talk if I was to be of help. I began by having Bill imagine that the warring parts were like two characters on a stage. I asked him to describe everything he could about each character—what it wore, its age, the expression on its face. Then I had him invite them into the room. The environmentalist sat stage left, sensitive features, longish hair. The property rights advocate stood more distant, stage right, stockier in build, baseball cap tucked between his crossed arms. After a bit, he too sat down.

I instructed Bill to turn to the two figures and describe the issue he wanted to address. After a bit of initial self-consciousness, Bill proceeded to talk with them about the land, the new regulations, the deep conflict he felt. Then I suggested that he go over to each chair and speak as that character—become it and give voice to what it felt about the questions at hand. I had him return to his own chair when each character had said its piece and from there to respond to the chair that had spoken and follow up with any further questions he might have. I instructed him to let himself be surprised by what each character might say.

This back and forth went through several iterations, first Bill speaking, then in turn, each of the parts. The character in the left chair spoke of the importance of protecting the environment in its natural state. The character on the right argued that government had no right to dictate what a person did with private property. Both expressed a longing to live in such a beautiful place. As the dialogue progressed, Bill’s relationships with each of them deepened. He became increasingly able to find a place in himself where he could both respect what each character had to say and see limits to its helpfulness. After some time, Bill again turned to me. He said he felt a bit disoriented, but that the conversation had helped. He commented that much of what the two characters said had indeed surprised him—and moved him. He found it particularly enlightening that each character seemed essentially well-intentioned. Before he had framed the environmental/property rights conflict as a battle between good and ignorance (if not worse). The work showed him that it was more accurately a battle between competing goods. Initially, it had been hard for him not to identify with the environmentalist, but, with time, he recognized that in fact each figure had important things to say.

The brief piece of work hadn’t given Bill a final answer for how to approach the property issue. But it had given him a more solid place to stand for making needed decisions. He had begun to see a more full and creative picture.

Later I asked Bill what broader implications the exercise might have for his professional efforts. We decided to continue with the hands-on approach. I tossed him particularly thorny questions that pitted environmental concerns against property rights concerns. His task was to hold his Whole-Person chair, and from there to use his two “consultants” to help him determine the most effective and fair approach. The result in each case was a deeper understanding of the dilemmas involved and, in several instances, novel solutions.

This example is highly simplified. Such work most often involves more parts than just two, and it may take several months of work before a person can sit solidly in the Whole-Person—whole-box-of-crayons, Integrative Meta-perspective—chair. But the example illustrates a general type of method that is both straightforward and highly effective.

Sometimes more parts are appropriate simply because the questions at hand involve more than two aspects. But it is also the case that people with different personality styles tend to work best with different degrees of differentiation. With some temperaments, having just a couple of characters in the room will prove most effective; with others, as many as seven, eight, or more.

As a therapist, I draw frequently on this kind of approach. I don’t know of other techniques that apply all of intelligence’s multiple aspects so simply and unobtrusively. I also don’t know of other ways of working that so directly support culturally mature perspective. It does so not just through what is said, but through every aspect of the approach, even the layout of the room. Of particular importance, the fact that I as a therapist speak only to the Whole-Person chair (one of those rules) means that my relationship with the client directly models and affirms Whole-Person relationship. Through the work, culturally mature perspective and responsibility become directly acted out and embodied.

Ongoing work with this kind of approach alters not just how a person engages specific issues, but also how he or she engages reality more broadly. The work becomes like lifting weights to build the “muscles” of culturally mature capacity. One of the litmus tests for success with this kind of approach is the appearance of culturally mature shifts with regard to questions that have not been directly discussed.

This same general kind of approach can also be applied to working with more than one person. I often use related methods when assisting groups where contentious issues have become polarized, or with groups where people wish to address many-sided questions that require careful, in-depth inquiry. When working in this way, I place individuals or small subgroups around the room to represent the various systemic aspects of the question at hand (the various characters/crayons). Another subgroup, seated in a circle around the smaller groups, is assigned two tasks—first to engage these subgroups in conversation to clarify their positions, and then to articulate a larger systemic perspective and explain how that perspective could be translated into right and timely action.

These various Parts Work techniques might seem to represent a specifically psychological kind of methodology. But in potential, they have much broader application. Because of the particular ways they are structured and the Whole-Person relationship the facilitator maintains with the individual or group doing the work, such approaches could ultimately be used anywhere engendering culturally mature capacities is an appropriate objective. I think most immediately of educational settings. While today we are not at the place where people would be comfortable utilizing these kinds of approaches in schools, it could be powerful to do so. Such methods would be most obviously a good fit where the task was interdisciplinary learning. But in the end they could be just as useful with education that focuses on particular kinds of knowing, such as religious education or the education of scientists.