Adapted from Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future

How do best talk about how culturally mature perspective alters understanding? Most simply, such perspective lets us more directly address life’s bigness. But we need more precise ways to speak about it. Our question is part of an important larger question. Cultural Maturity’s cognitive changes not only produce new conclusions and change how we think they alter our understanding of what makes something true at the most basic of levels. We need to better understand just how this is so.

We can come at making sense of how Cultural Maturity’s changes alter our understanding of truth itself in multiple ways, each with its lessons to teach. One of the most useful draws on a basic observation: Needed new understandings of every sort require that our thinking create links, “bridges”—and not just between phenomena we’ve regarded as different, but often between things that before now we’ve treated as complete opposites—as polarities.

F. Scott Fitzgerald proposed that the sign of a first-rate intelligence (we might say a mature intelligence) is the ability to hold two contradictory truths simultaneously in mind without going mad. His reference was to personal maturity. But this capacity is such an inescapable part of culturally mature perspective that we could almost say it defines it.

Effective global policy requires “bridging” ally and enemy. It also bridges political ideologies and, in the end, even usual ideas about war and peace. Mature gender identity and love link masculine with feminine, and individuality with connectedness. New approaches to leadership create bridges between leaders and followers, and as needed greater transparency occurs, bridges also appear between the internal worlds of organizations and between organizations and the larger world. The needed new kinds of relating, values, and understanding don’t require that we consciously recognize that bridging is taking place, or even that polarities are involved. But they do require that we somehow get our minds around a larger picture and act from it. (My 1992 book, Necessary Wisdom, uses this simple observation as a lens to examine a broad array of contemporary issues.)

We can think of Cultural Maturity’s point of departure as itself a bridging dynamic: We step back and see the relationship of culture and the individual in more encompassing terms. Cultural Maturity bridges ourselves and our societal contexts (or put another way, ourselves and final truth). It is through this most fundamental bridging that we leave behind society’s past parental function.

It is important that we not misinterpret this. Cultural Maturity is not about culture’s role disappearing. Rather it is about a new and deeper recognition of how individual and culture relate—about how, through our thoughts and actions, we create culture, and how personal and cultural realities each inform the other. It is also about making our understanding of both being an individual, and being an individual who lives in an interpersonal context, more dynamic and complete.

This most encompassing linkage holds within it a multitude of more local “bridgings.” Nothing more characterized the last century’s defining conceptual advances than how their thinking linked previously unquestioned polar truths. Physics’ new picture provocatively circumscribed the realities of matter and energy, space and time, and object with its observer. New understandings in biology linked humankind with the natural world, and by reopening timeless questions about life’s origins, joined the purely physical with the organic. And the ideas of modern psychology, neurology, and sociology have provided an increasingly integrated picture of the workings of conscious with unconscious, mind with body, self with society, and more.

Recognizing the fact of polarity by itself is not new. Our familiar Cartesian worldview is explicitly dualistic. Nor is the idea that polarity might be pertinent to wisdom new. That is, in fact, a quite ancient recognition. Epictetus observed that “Every matter has two handles, one of which will bear taking hold of, the other not.” But what I describe here is new, and fundamentally.

In modern times, even if we have acknowledged the basic fact of polarity, most often we’ve missed that the sides of polarity might relate. And certainly we’ve missed that they might relate in ways that produce today’s needed more mature and complex picture. We’ve assumed that it is right to think of minds and bodies as separate even though daily experience repeatedly proves otherwise. And we’ve accepted that a world of allies and “evil empires” is just how things are even as one generation’s most loathed of enemies becomes the next generation’s close collaborator.

The fact that we could miss polarity’s larger picture might seem odd. Why would we assume that reality is anything but whole? It turns out that there is a good reason. In fact, polar perception has an essential developmental function—in human change processes of all sorts. Indeed, it is critical to the mechanisms of development.

Appreciating the key role projection has historically played in human understanding helps us make the connection—both with regard to polarity’s role in times past and to precisely what changes with maturity. Projection involves polarity, a fact that becomes particularly tangible when mythologizing’s ardencies are involved. Projection in times past has served us. But one of the things that most marks Cultural Maturity is how its changes help us get our minds around the larger relationships that projection has kept us from recognizing. Mature thought in our individual lives does so in an important but circumscribed sense; culturally mature thought does this with regard to understanding more generally.

Implied in all of this is the essential recognition that the “problem” with polarity is not an intrinsic difficulty. Rather it is an expression of where we reside in the story of understanding. In times past, polarity worked. The polar tensions between church and crown in the Middle Ages, for example, were tied intimately to that time’s experience of meaning. With the Modern Age—and just as right and timely in their contributions—we saw Descartes’ cleaving of truth into separate objective and subjective realities, along with the competing arguments of positivist and romantic worldviews. And while here I’ve strongly emphasized the outmodedness of petty ideological squabbles between political left and political right, I am just as comfortable proposing that such squabbles, in their time, were creative and essential. They drove the important conversations. The problem is not with polarity itself, but with its inability in our current time to effectively generate truth and meaning.

If the relationship between “bridging” and complexity is to make ultimately useful sense, we must take care to avoid confusing “bridging” in this sense with a couple more familiar outcomes. Bridging as I am speaking of it is wholly different from averaging or compromise, walking the middle of the road. And just as much it is different from simple oneness, the callapsing of one pole into the other as we commonly see with more spiritual interpretations. Bridging, as I use the word, is about consciously engaging the larger whole-ball-of-wax picture.

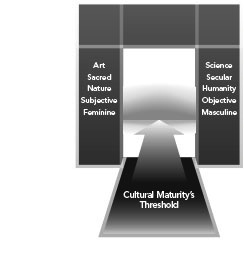

I often make use of a simple diagram to emphasize these differences. It depicts Cultural Maturity’s threshold as literally a doorway, with each side of the doorway’s frame representing one half of a polar relationship:

Cultural Maturity’s Threshold

The term bridging might seem to suggest that our interest lies with joining the doorway’s two sides. But something quite different is necessarily involved. The doorway’s lintel could adequately represent either of our two misinterpretations. But joining the doorway’s two sides leads us nowhere—certainly nowhere pertinent to our desired destination. Cultural Maturity’s changes require that we make our way up to the doorway, step over the doorway’s threshold, and proceed into a reality that is not just more inclusive, but of an entirely different sort. Bridging in this sense we have interest in reflects this wholly different sort of action.

A good place to recognize such bridging’s fundamental newness is the way culturally mature conclusions can on first encounter seem paradoxical. Such apparent paradox is most obvious with ideas that are not so much about us—for example, how cutting-edge notions in physics are perfectly comfortable with something being at once a particle and a wave. But it is just as inescapably present with explicitly human concerns. Mature love makes us both more separate and more deeply connected; mature leadership is both more powerful and more humble than what it replaces.

Culturally mature perspective makes clear that this paradoxical appearance, again, is nothing mysterious. It simply reflects polarity’s necessary role in how we think. Blindness to polarity constrains us within a world of absolutes (and projections). Cultural Maturity’s threshold highlights the existence of polarity and alerts us to the fact that a polar picture is inadequate. Step over that threshold and into mature territory and things become more of a whole—a more dynamic and multifaceted kind of whole than we are used to, but also one in which the opposites of paradox are not ultimately at odds.

The essential recognition for our project is that such bridging makes us more. And today it makes us more in exactly the “idea whose time has come” sense essential to a vital and healthy future. We can put the result specifically in terms of complexity. Bridgings of any sort take an either/or world and replace it with a picture that is more multi-hued and rich in its implications than we could have understood in times past.

We find the same result whether the defining polarity is conceptual or one that serves to order values and relationships. Bridge matter and energy and the result is a world of intricately interrelated particles and forces ever-surprising in what they have to reveal. Bridge ally and enemy and we find a world of people who share a common humanity, but who at the same time often remain profoundly foreign to our understanding—in wonderful and particular ways. In this new reality complexity cannot be escaped, and past, more limited ways of understanding gradually lose their appeal. When bridging is something we are ready for, we experience what it reveals as a gift—and one of ultimately profound significance.

All of this brings us very close to a particularly provocative question, one to which we will later return. We could think of it as the question at the heart of philosophy—indeed at the heart of understanding itself. In its Modern Age version, it pits more rationalist/reductionist/positivist sorts on one hand against more romantic/idealist/holistic types on the other. Here is how Robert Pirsig put it in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry Into Values (1974). Think of the world as a handful of sand arranged in separate piles. In Pirsig’s description, “classical understanding is concerned with the piles and the basis for sorting and relating them,” while “romantic understanding is directed toward the handful of sand before the sorting began.” Pirsig proposes that, “what has become urgently necessary is a way of looking at the world that does violence to neither of these two kinds of understanding and unites them into one.”

He is, of course, far from the first to pose this problem—but the answer has seemed always just out of reach. That the best of contemporary understanding bridges polarities suggests we are getting closer at least in application, if not on a more abstract level. It follows from the concept of Cultural Maturity that in time we should also see approaches to understanding that succeed more conceptually—and at an overarching, all-encompassing scale.