Creative Systems Theory takes us beyond the mechanistic assumptions of Modern Age thought and allows us to think in ways that better reflect that we are alive—and human. It also argues that finding ways to make this kind of leap will be critical to effective future understanding. And it describes how Cultural Maturity, a needed growing up in how we understand and act that follows from the theory, offers that we might think in ways that are more dynamic and complete.

Just how it succeeds with this essential leap is the topic of my most recent book, Intelligence’s Creative Multiplicity: and Its Critical Role in the Future of Understanding. Key to the theory’s approach is the very particular way that it frames the workings of intelligence. A first observation—that Intelligence has multiple aspects—is not at all original. It is hard to miss that we are more than just rational beings. But a second kind of observation is specifically new and radical. The theory argues that human Intelligence is organized “creatively.”

Its a notion that should not wholly surprise us given that what most defines us as creatures is the audacity of our toolmaking, meaning-making natures. Creative Systems Theory proposes that we are the uniquely creative creatures that we are not just because we are conscious, but because of the specifically generative way that the various aspects of our intelligence work, and work together.

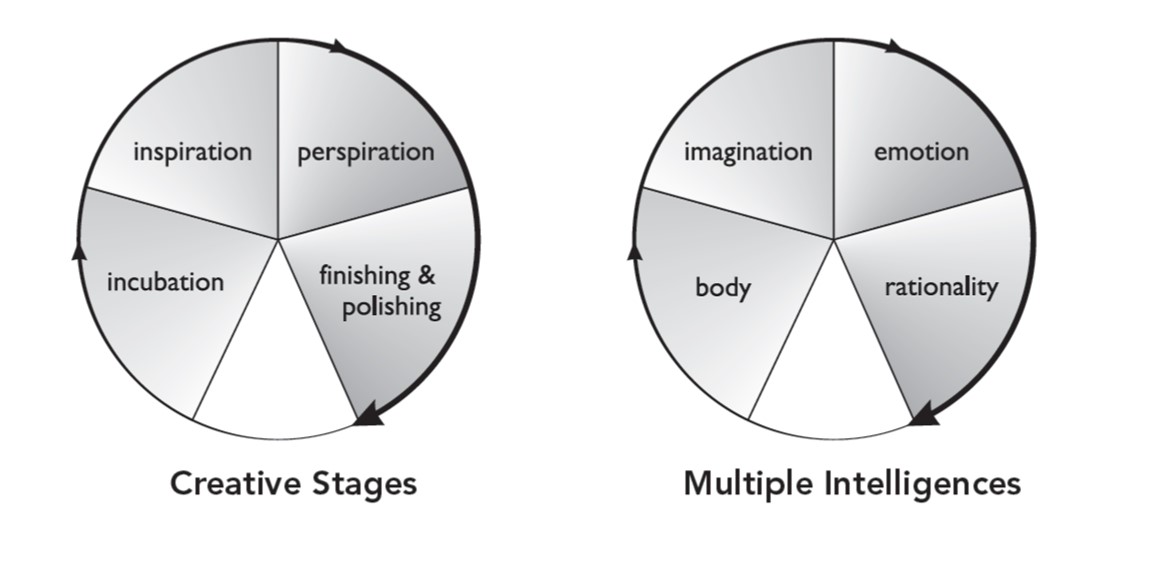

The theory identifies four basic types of intelligence. For ease of conversation, we can refer to them as the intelligences of the body, the imagination, the emotions, and the intellect. (CST uses fancier language.) It proposes that these different ways of knowing represent more than just diverse approaches to processing information. They are the windows through which we make sense of our worlds. And more than this, they describe the formative tendencies that lead us to shape our worlds in the ways that we do.

The following diagram from the book depicts these links between the intelligence’s multiplicity and the workings of formative process:

Formative Process and Intelligence’s Creative Multiplicity

A brief look at a single creative process—say doing a piece of sculpture or writing a book—helps clarify this relationship. In subtly overlapping and multi-layered ways, the process by which any creative product comes into being goes through a progression of creative stages and associated sensibilities. Creative processes unfold in varied ways, but the following outline is generally representative:

—Before beginning, our sense of things is likely to be murky at best. Creative processes begin in darkness. We may be aware we have something we want to communicate, but we are likely to have only the most beginning sense of just what that might look like. This is creativity’s “incubation” stage. The dominant intelligence here is the kinesthetic, body intelligence. It is like we are pregnant, but don’t yet know with quite what. What we do know takes the form of “inklings” and faint “glimmerings,” inner sensings.

—Generativity’s second stage propels the new thing created out of darkness into first light. We begin to have “ah-has”—our minds flood with notions about what we might express and possible approaches for expression. Some of these first insights take the form of thoughts. Others manifest more as images or metaphors. In this “inspiration” stage, the dominant intelligence is the imaginal—that which most defines art, myth, and the let’s-pretend world of young children.

—The next stage leaves behind the realm of first possibilities and takes us into the world of manifest form. We try out specific structural approaches. And we get down to the hard work that real creativity always requires. This is creation’s “perspiration” stage. The dominant intelligence is different still, more emotional and visceral—the intelligence of heart and guts. It is here that we confront the hard work of finding the right approach and the most satisfying means of expression.

—Generativity’s fourth stage is more concerned with detail and refinement. While the created object’s basic form is established, much yet remains to do. Rational intelligence orders this “finishing and polishing” stage. This period is more conscious and more concerned with aesthetic precision than the periods previous. It is also more concerned with audience and outcome. It brings final focus to the creative work, offers the clarity of thought and nuances of style needed for effective communication.

—Creative expression is often placed in the world at this point. But a further stage—or more accurately, an additional series of stages—remains. It is as important as any of the others—and of particular significance with mature creative process. Creative Systems Theory calls this further generative sequence Creative Integration. With the process of refinement complete, we can now step back from the work and appreciate it with new perspective. We become better able to recognize the relationship of one part to another. And we become more able to appreciate the relationship of the work to its creative contexts, to ourselves and to the time and place in which it was created. We might call creativity’s integrative stages the seasoning or ripening stages. Creative Integration forms a complement to the more differentiation-defined tasks of earlier stages—a second half to the creative process. Creative Integration is about learning to use our diverse ways of knowing more consciously together. It is about applying our intelligences in various combinations and balances as time and situation warrant, and about a growing ability not just to engage the work as a whole, but to draw on ourselves as a whole in relationship to it. As wholeness is where we started—before the disruptive birth of new creation—in a certain sense Creative Integration returns us to where we began. But because change that matters changes everything, this is a point of beginning that is new—it has not existed before.

Creative Systems Theory applies this relationship between intelligence and formative process to human understanding as a whole. It proposes that the same general progression of sensibilities we see with a creative project orders the creative growth of all human systems. It argues that we see similar patterns at all levels—from the growth of an individual, to the development of an organization, to culture and its evolution. A few snapshots:

—The same bodily intelligence that orders creative “incubation” plays a particularly prominent role in the infant’s rhythmic world of movement, touch, and taste. The realities of early tribal cultures also draw deeply on body sensibilities. Truth in tribal societies is synonymous with the rhythms of nature and, through dance, song, story, and drumbeat, with the body of the tribe.

—The same imaginal intelligence that we saw ordering creative “inspiration” takes prominence in the play-centered world of the young child. We also hear its voice with particular strength in early civilizations—such as in ancient Greece or Egypt, with the Incas and Aztecs in the Americas, or in the classical East—with their great mythic forces and symbolic tales.

—The same emotional and moral intelligence that orders creative “perspiration” tends to occupy center stage in adolescence with its deepening passions and pivotal struggles for identity. It can be felt with particular strength also in the beliefs and values of the European Middle Ages, times marked by feudal struggle and ardent moral conviction (and, today, in places where struggle and conflict seem to be forever recurring).

—The same rational intelligence that comes forward for the “finishing and polishing” tasks of creativity takes new prominence in young adulthood, as we strive to create our unique place in the world of adult expectations. This more refined and refining aspect of intelligence stepped to the fore culturally with the Renaissance and the Age of Reason and, in the West, has held sway into modern times.

—Finally, and of particular pertinence to the concept of Cultural Maturity, the same more consciously integrative intelligence that we see in the “seasoning” stage of a creative act orders the unique developmental capacities—the wisdom—of a lifetime’s second half. We can also see this same more integrative relationship with intelligence just beneath the surface in our current cultural stage in the West in the advances that have transformed understanding through the last century.

We associate the Age of Reason with Descartes’s assertion that “I think, therefore I am.” We could make a parallel assertion for each of these other cultural stages: “I am embodied, therefore I am”; “I imagine, therefore I am”; “I am a moral being, therefore I am”; and, if the concept of Cultural Maturity is accurate, “I understand maturely and systemically—with the whole of myself—therefore I am.”

Creative Systems Theory describes how the application of a Creative Frame lets us think about human systems of all sorts in ways that better reflect our living complexity. It also makes a claim with regard to the elegance of such notions that might seem particularly audacious. In what might seem a paradox, while the thinking of Creative Systems Theory is more complex and nuanced than usual understanding, at the same time it is in important ways simpler. Einstein once observed that the whole of his thinking followed from the question of what experience would look if he were riding on a beam of light. The whole of Creative Systems Theory—including the radical concept of Cultural Maturity—can be understood to follow from the question of what truth becomes if intelligence is creatively ordered.